Week 1 Introduction - Whose Geography? (KY)

Section outline

-

This session is divided into two parts. In the first half you will have some time to introduce yourself to the group and discuss the group’s backgrounds and interests in the module. We’ll also go through the module itself in more detail, including its structure, how the sessions work, the assessment, what’s expected of you and what you can expect from the module. In part two we’ll then turn to reflect more generally on the relationship between geography, theory and practice. We will also be addressing the idea of what “research” actually “is”.

Key questions for discussion in today’s lecture, which are in effect the principles issues we will be discussing in this first half of the Semester, are the following:

1) What does it mean to think geographically? How does where we think geography from matter in terms of who gets to be recognized as a maker of geographical knowledge, and who gets to be recognized as a 'subject' of geographical knowledge?

2) How have approaches to geographical research changed over the last 100 years? How is the making of geographical knowledge contested and resisted?

3) How does this reflect the influence of different social, political and intellectual contexts and the long histories of colonialism and empire?

4) What particular philosophies and theories have influenced geography the most? What are the challenges to these theories?

5) What does it mean (for your research) to adopt one kind of theoretical perspective – one way of thinking geographically – over another? Or, how do methods matter?

6) How can geography be decolonized and what is the role of the university in this praxis?

-

Please read and comment on this document before the class, specifically, what does deconization mean in the context of teaching and learning geographical theory and practice, and learning geographical methods.

This is a working 'live' document developed by staff and postgraduate students, as a starting point for rethinking how and what geography we teach in the context of making an anti-racism classroom.

35.6 KB -

1. Quotation: Pull out a few key quotations from the text or videos that you think are central to the author's implicit or explicit argument.

2. Argument: In five or six sentences, state the author's argument. Be sure to include both what the author is arguing for and arguing against.

3. Question: Say why you think these are important points and how they makes us think differently about geography, space or place. Raises any questions you think are not fully and could be developed.

4. Connection: Connect the argument of this text to broader methodological approaches and other readings from your research.

5. Connection: Connect the argument to a specific example of a contemporary geographical issue in society.

-

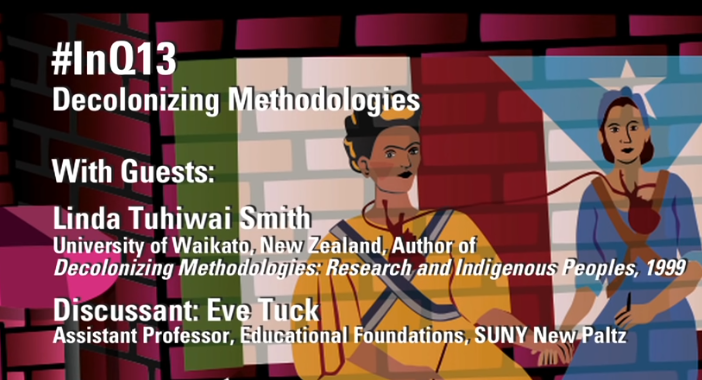

Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith shares insights into

indigenous knowledge, language revitalization, decolonizing research

practices, and how to "make knowledge live.”

Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith shares insights into

indigenous knowledge, language revitalization, decolonizing research

practices, and how to "make knowledge live.” -

Indigenous peoples and the scientific gaze.

-

Dr. Kim TallBear from University of Alberta and Canada Research Chair for Indigenous Peoples, Technoscience and Environment discusses innovate ideas to advance science and technology opportunities and careers for Indigenous communities.

-

Lakota historian Nick Estes on how two centuries of indigenous resistance created the movement proclaiming “Water is life.” Estes’s new book is titled Our History Is the Future. He is a co-founder of the indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe.

-

This is a timeline that might be used to represent the development of key geographical thinkers and the shape of the discipline over the last 100 years. What do you notice about this timeline? Who does it represent? What geographies are missing from this understanding of geographical history? What is the identity of the geographers represented?

35.5 KB -

2.0 MB