MBBS COVID Information

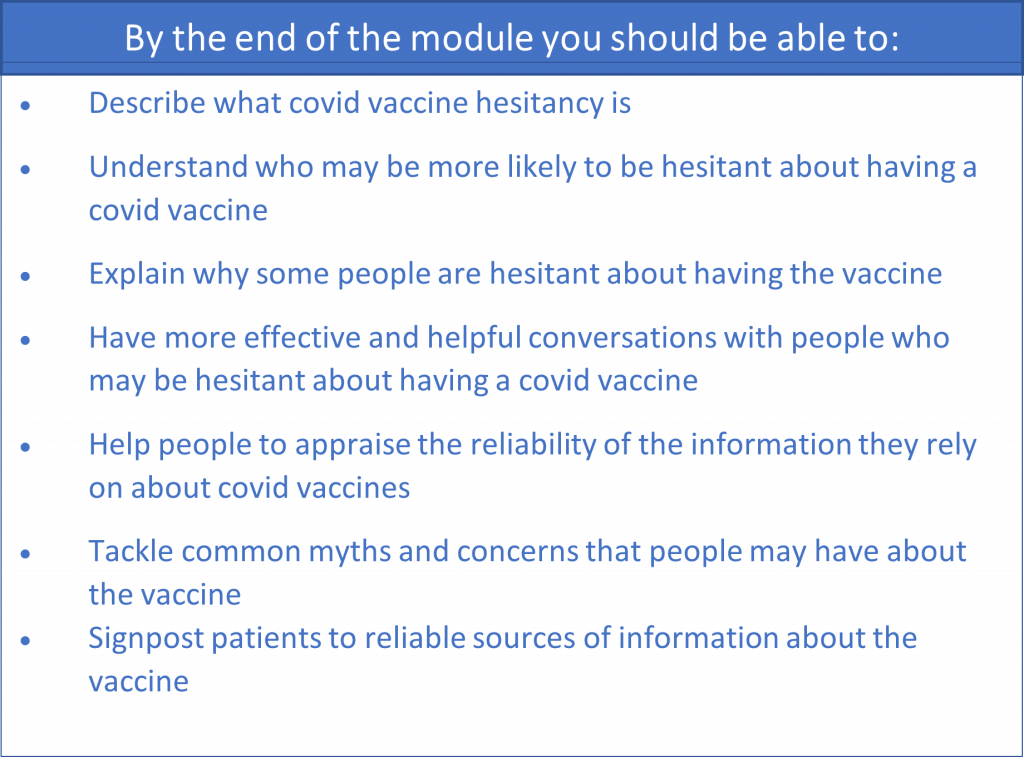

Section outline

-

-

-

An important step in talking to people about vaccine hesitancy is to establish where they are on the spectrum of attitudes towards having the Covid vaccine.

In this exercise, you are asked to match the patients to the most appropriate descriptions of where they are on the vaccine hesitancy scale

-

-

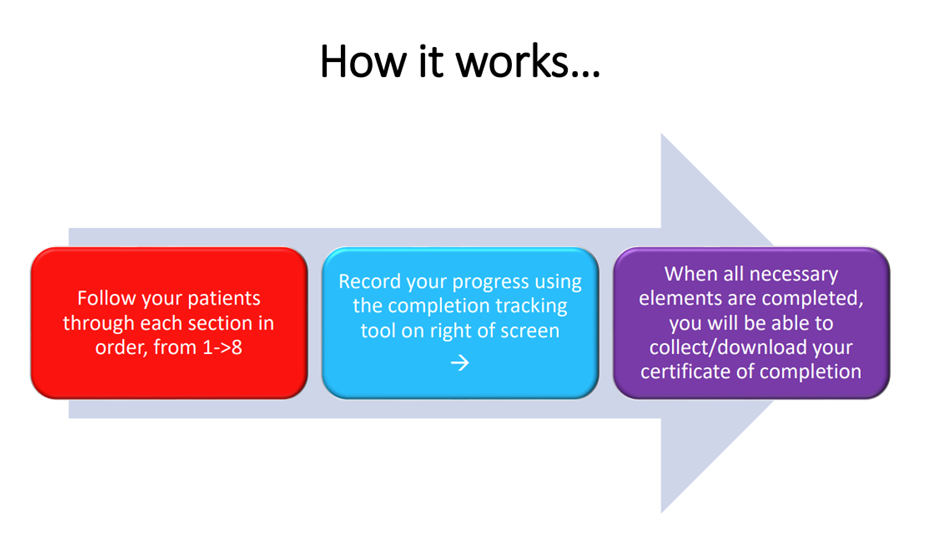

Have a look at this visual summary of common concerns about Covid Vaccines and some tips on addressing them and links to great resources. Follow the sections in order: 1-5.

258.3 KB -

A brief editorial from BMJ exploring why some ethnic groups are more likely to be vaccine hesitant, and how we can try to tackle it

462.9 KB -

Barely a month into England's coronavirus vaccine programme, a stark inequality began to reveal itself. Black people were less likely than any other group, and half as likely as white people, to have had the jab.

By April 2021 , 64% of black over-50s had been vaccinated compared with 93% of white people of the same age. The reasons for this are complex. Unethical medical treatment in the past, ongoing discrimination and personal experiences of insensitive treatment by the NHS are all believed to play a part.

But doctors, researchers and campaigners who spoke to the BBC said they feared black communities were being blamed.

-

-

Please post a brief comment to share with other learners. Click on "reply" below to post your thoughts. Please answer these 2 questions in your post:

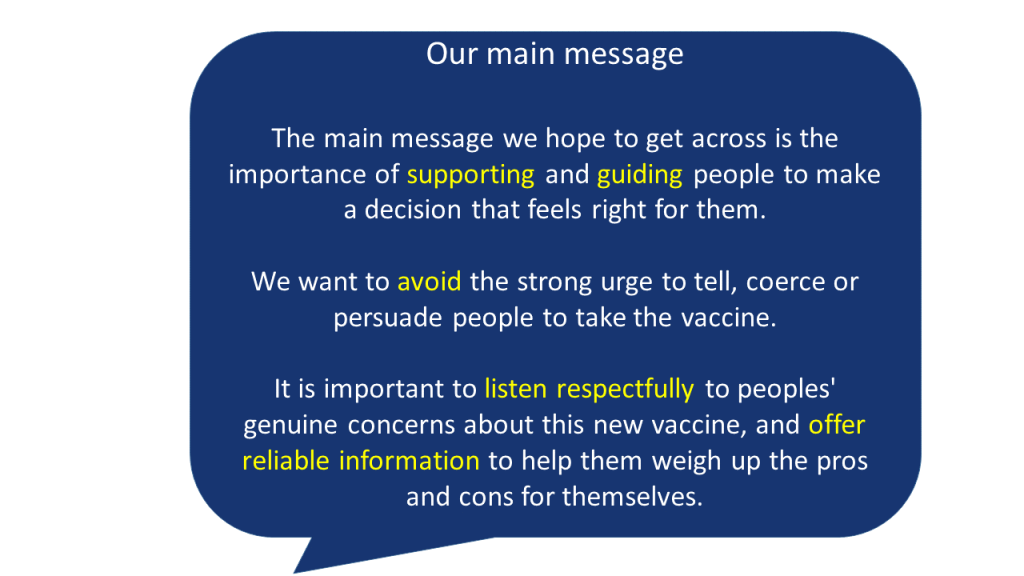

1. What is your role in these conversations? Please post a sentence or two describing what you think your role is when you talk with someone who is hesitant about having the Covid Vaccine. What are you trying to achieve?

2. How do these conversations make you feel? You may also wish to share a few thoughts about how these conversations make you feel; or how you imagine they might make you feel. Are you anxious, frustrated, angry, excited?

-

-

Here are three role play scenarios for you to practice or to reflect on. It is a chance to put into practice some of the techniques you have learned about. You could do these with a friend or colleague in role; or just practice out loud what you might say to the patient in the cartoon strip

-

-

SIDE EFFECTS OF COVID-19 VACCINES

It is important to let patients know about common side effects as well as possible benefits of the vaccine.

This information is from the NHS:

The COVID-19 vaccines approved for use in the UK have met strict standards of safety, quality and effectiveness.

They can cause some side effects, but not everyone gets them.

Any side effects are usually mild and should not last longer than a week, such as:

- a sore arm from the injection

- feeling tired

- a headache

- feeling achy

- feeling or being sick

More serious side effects are very rare.

Find out more about COVID-19 vaccines safety and side effects

-

Concise evidence-based answers to common Covid vaccine concerns, available in many languages. From the Islamic Medical Association

[NB They use the term "myths", but feedback from our community suggests that this can seem dismissive of peoples' genuine concerns. When speaking with patients, it is probably more helpful to refer to them as "concerns" or "rumours" rather than myths]

-

After you have browsed the collection of videos and articles representing the views of the vaccine hesitant, record a short video in which you offer people reliable information using the following structure:

1 Argument or concern against vaccination.

2 Counter-argument, supporting vaccination

-

Evidence-based information about the Covid-19 Vaccine, from the NHS

-

Experts from Johns Hopkins Medicine review some common myths circulating about the vaccine and clear up confusion with reliable facts.

-

-

There is lots of information online that is poor quality, incorrect, false (misinformation), deliberately deceptive or potentially harmful (disinformation). So it is really important to have the skills to evaluate anything you find.This interactive page introduces three useful techniques for evaluating the information you meet online. You may also find them helpful when talking with patients about how to judge the reliability of their information sources:1 Lateral Reading2 S.I.F.T and3 Fact-checking

-

-

-

We would really appreciate your feedback about the module if you can spare a few moments to say what you liked and what we could do differently. Thank you so much.