Expanded Reference Guide

| Site: | QMplus - The Online Learning Environment of Queen Mary University of London |

| Module: | English & Drama Writing and Reference Guide |

| Book: | Expanded Reference Guide |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 7:51 AM |

Description

Fuller guide to referencing in SED (e.g. film, online and electronic sources), including examples of how to present quotations, footnotes (and how to limit footnotes) and bibliographies in your essays.

1. Introduction

Why should we reference?

1. Because that’s what professional writers do.

Every profession has its professional practice and a number of writing professions follow style guides to ensure that the high standards of the profession are kept up. Proper referencing helps to make the difference between a rough draft and a finished work.

2. Because your work forms part of the critical, or secondary, literature.

In academic writing we quote and reference work properly in order to engage with academics that precede us and so that the reader can find what we are referencing and continue the conversation. Your references should allow the reader to find your sources as quickly and easily as possible.

3. Because there are consequences if you don’t.

For your degree assessment, references indicate to your markers and examiners the extent to which you have mastered the scholarly practices of your discipline.

They also show that you are referencing other writers’ work and ideas (which is really good), and not plagiarising them (which is to be avoided). The Student Handbook states that

Plagiarism means copying something that somebody else has written, or taking their ideas, and trying to pass them off as your own work. Plagiarism is a serious offence and carries severe penalties, which can in some circumstances lead to a student being dismissed from the College. You can also commit plagiarism by using most or part of one of your own essays for a module and simply copying it into an essay for another module.

The full wording of the policy on plagiarism, including the penalties, can be found here.

SED style

In the School of English and Drama we use a version of the MHRA (Modern Humanities Research Association) Style Guide. You can download the complete MHRA Style Guide from the MHRA website but, for ease of reference, we encourage you to work from the SED Quick Reference Style Sheet, the SED Quick Reference Guide for theatre, television, social media etc. and this Expanded SED Reference Guide.

SED's COLT (Citation On-Line Tutorial)

If you want to test your knowledge of referencing, the School of English and Drama has developed an interactive tutorial. A basic and an advanced tutorial are available and these can be accessed here.

2. How to use quotations and references effectively

Quotations

Quotations should not be used uncritically in an essay. Here is a list of 'Do's and Don'ts' to help you discover the potential of quotations.

Do:

- Choose your quotations with care, whether from literary texts or from critics' arguments – finding the quotation that exactly illustrates your point can be an art.

- Set up and introduce your quotations so that the reader does not get lost.

- Critically evaluate and question quotations from critics' arguments as well as literary texts.

- Set quotations from differing critics against each other to highlight controversy and make clear which you agree with most.

- Quote accurately, maintaining the original spelling, punctuation, capitalisation etc.

- Quote exactly from whatever source has been selected as the most appropriate: unless you state otherwise, it must be the precise edition listed in your bibliography.

Don't

- Quote out of context – make sure you know how the quoted text fit into the critic’s argument.

To integrate or not to integrate your quotations

It is good practice to integrate quotations into your sentences, as long as this is in a way that the grammar of your sentence and the internal grammar of the quotation work together to form a coherent sentence.

You are permitted to make very small changes to the grammar of the quotation in square brackets in order to make it fit the sentence – as in the first version of the example below. However, it is probably better practice to change the grammar of your sentence to fit the quotation – as in the second version below.

Jane's work 'condense[s] itself as he [Rivers] proceed[s] and assume[s] a definite form under his shaping hand'.

When talking with Rivers, Jane reflects that her work 'condensed itself as he proceeded and assumed a definite form under his shaping hand'.

If you cannot make this work, it might be better to include more of the quotation and to 'block quote' it as for a longer quotation (see next section, how to present quotations).

Long 'block' quotations can be very useful when close reading as, in the text following this, you can pull out words or phrases from the already referenced quotation more easily, as in the example below:

She was standing, waving her arms, above the battlements, and shouting out till they could hear her a mile off: I saw her and heard her with my own eyes. She was a big woman, and had long black hair: we could see it streaming against the flames as she stood. I witnessed, and several more witnessed Mr Rochester ascend through the skylight on to the roof: we heard him call ‘Bertha!’ we saw him approach her; and then, ma’am, she yelled, and gave a spring, and the next moment she lay smashed on the pavement (451).

In this passage Bertha is presented as a wild thing, larger than life, and barely human. Her irrationality is signalled by her 'shouting' and 'yelling' – unlike Rochester, her utterances are not given shape as recognisable speech – and she is seen to be excessive, in that she is a 'big' woman, with uncontrollable hair that 'streams', and she is so loud that she can be heard 'a mile off'. The violence of the passage is encapsulated in the image of Bertha 'smashed on the pavement'.

References

Where you do not wish to quote a source, but do want to refer the reader to more scholarship or information, use a footnote to reference this. These references might:

- indicate to the reader the source of a quotation or a more extended account of the subject mentioned in the text.

- cite authority in support of a statement, opinion or hypothesis.

- direct the reader to opinions on controversial issues contrary to those expressed in the text.

However, try to avoid these footnotes becoming too discursive and expository. Always ask yourself if the material is relevant and, if so, whether it ought to be contained in the main body of the essay. Footnotes are included within your word count.

3.1. When quoting prose...

Short quotations (not more than forty words) should be enclosed in single quotation marks and run on with the main text.

Examples:

1. Bhabha argues that 'Mimicry is at once resemblance and menace'.1

2. While Watt does not fully challenge the claim that Defoe is ‘our first novelist’,2 Gallagher complicates the matter when she draws attention to Robinson Crusoe’s lack of two things – ‘(1) a conceptual category of fiction, and (2) believable stories that did not solicit belief’3 – that she believes are essential features of novels.

3. Looking up, Yorick perceives 'a starling hung in a little cage – "I can't get out," said the starling'.4

4. In Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Alice asks herself, ‘“Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?” and sometimes, “Do bats eat cats?”’.5

5. Seth Koven has written persuasively about the concentration of late nineteenth-century philanthropists on hygiene in homes, suggesting they were more an ‘army of social housekeepers’ rather than a spiritual army fighting to raise them to heaven.6

Note:

- It is good practice to make your quotations part of your sentence, as in the examples above.

- Quotations used in this way are not required to end with punctuation – follow the rules of punctuation for your whole sentence (the comma after ‘our first novelist’ in example two is there as part of the grammar of the sentence) – except when the quotation ends with a question or exclamation mark.

- Footnote numbers should be in superscript (this is automatic when using the insert footnote tool in MS Word) and should be placed after the quotation and any punctuation, except in the case of dashes, as in example two above. Where possible it is best to place the footnote number at the end of the relevant sentence, as in example five.

- For quotations within quotations, double quotation marks should be used, as in examples three and four above.

Long quotations (forty or more words) should be broken off from the preceding and following lines of typescript. They should be indented five spaces, and single-spaced. They should not be placed within quotation marks.

Examples:

1. In his study Imagining the Penitentiary, Bender emphasises how the new prisons worked as a narrative of reformation:

the reformers aimed to reshape the life story of each criminal by measured application of pleasure and pain within a planned framework. [...] Upon entering one of the new penitentiaries, each convict would be assigned to live out a programme or scenario.7

This model reproduced many features of the narrative structure of the novel.

2. Dickens uses literary techniques, such as anthropomorphism and repetition, to build a scene, as can be seen in the beginning to Bleak House:

Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards, and hovering in the rigging of great ships. [...] Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little ’prentice boy on deck.8

Note:

- If any words are omitted in a quotation the omission must be marked by an ellipsis within square brackets '[...]' as in the examples above. It is not normally necessary to use an ellipsis at the beginning or end of a quotation.

- The quotation should end with a full stop – or a question mark if that was the original punctuation.

- Start a new sentence after the quotation – it is asking too much of the reader to follow a sentence over a long quotation.

3.2. When quoting verse...

Short verse quotations (three lines or less) should indicate the original text’s line breaks by inserting an upright stroke with a space on each side ' / ' to separate lines, preserving initial capital letters if used.

1. It is implied in the lines ‘“Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!” / Quoth the raven, “Nevermore”’ that Poe’s narrator cannot escape his pain of lost love, which will haunt him forever.1

2. While the narrator in ‘Tulips’ wants to efface herself, she is forced to accept an identity – an ‘I’ – as the word play on ‘eye’ in the second stanza makes clear: ‘They have propped my head between the pillow and the sheet-cuff / Like an eye between two white lids that will not shut / Stupid pupil, it has to take everything in’.2

Note:

- Follow the same rules on punctuation and quotations within quotations as for short prose quotations.

Long verse quotations of more than three lines, even if less than forty words, should be indented and single-spaced, as for long prose quotations. The line breaks of the original text should be preserved.

1. In book thirteen of the 1805 Prelude Wordsworth suggests that a version of Nature’s sublime power can also be found within creative minds; nature’s sublime

is the express

Resemblance – in the fullness of its strength

Made visible – a genuine counterpart

And brother of the glorious faculty

Which higher minds bear with them as their own.3

2. John Donne diminishes the importance of the sun – and other natural forces – in comparison with man when he jokes

Thy beams so reverend and strong

[...]

I could eclipse them with a wink,

But that I would not lose her sight so long.4

3.

Poems

written in the ((((1950's by

charles

olsen

have/lots of stuff

like this

going on

on

on

it’s to do with breath and (other stuff that he writes about in

THE HUMAN uniVERSE)5

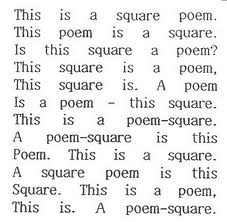

4. Some poems incorporate or create images, such as this example of concrete poetry by Bob Cobbing:6

Note:

- If you are starting in the middle of a line, leave a space and abide by the original capitalisation, as in example one.

- If you are missing out one or more entire lines, use a single ellipsis in square brackets to stand for that line, as in example two.

- If an original line is too long to fit onto one line, carry on to the next line but indent it five more spaces to make clear that it is part of the preceding line.

- Quotations of verse with irregular or unusual line spacing: as far as possible, you should try and reproduce the presentation of the verse as it appears on the page of your edition, as in example three. If this proves difficult, you could scan the text, or find it on google images, and include as an image, as in example four.

3.3. When quoting plays...

In general, follow the same rules as when quoting short and long prose (when quoting blank verse) – and short and long verse.

Prose examples:

1. Sidney Grundy’s Mrs Sylvester in The New Woman is adamant that she knows what men are like, making confident proclamations such as: ‘a man thinks of nothing but his stomach’.1

2. Ibsen’s character, Dr. Rank, is so convinced that his health has been affected by his heredity, that he feels he must sacrifice things like marriage and pleasure in life, much to the annoyance of Nora:

NORA You are quite absurd today. And I wanted you so much to be in a really good

humour.

RANK With death stalking beside me? To have to pay this penalty for another man’s

sin! Is there any justice in that? And in every single family [...] some such inexorable retribution is being exacted.2

Verse examples:

3. The fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream are said to wander ‘over hill, over dale / thorough bush, thorough briar’.3

4. Federico Garcia Lorca consciously used verse and prose for different effects; in Blood Wedding, verse takes over at the end of the play:

BRIDE O the four young men

Who carry death through the air!

MOTHER Neighbours!

LITTLE GIRL (at the doorway)

They’re bringing them now.

MOTHER It’s the same –

The Cross! The Cross!4

Note:

- In long prose quotations the character’s name is presented in small capitals, followed by a space, and second and subsequent lines of speech are indented, as shown in example two.

- When a stage direction follows a character name the space follows the stage direction instead of the character’s name.

- In long verse quotations the character’s name is indented and the verse lineation should be reproduced as accurately as possible, as in example four.

- Stage directions are italicised and presented in parentheses, as in example four.

4. Footnotes

This section gives information about how footnotes should appear when you are referencing the following sources:

4.1 Books

4.5 Footnoting plays and poems

4.6 Newspapers

4.8 Online and electronic sources

4.9 Film and cinema

4.10 Manuscripts

4.1. Books

When footnoting a book – either a primary text or secondary material – information such as the title and publication details should be given in the following order:

1. Author’s name (forename, surname, not abbreviated)

2. Title of book (in italics, in full, with all principal words capitalised)

3. Editor or translator (preceded by ‘ed. by’ or ‘trans. by’)

4. Edition (if other than the first, e.g. ‘2nd edn’, ‘rev. edn’)

5. Number of volumes in multi-volume publication (e.g. ‘5 vols’)

6. Details of publication, enclosed in parentheses, in this order and with this punctuation: (city of publication: publisher, date)

7. Volume number of the volume referred to (in capital roman numbers)

8. Page numbers (preceded by singular 'p.' or plural 'pp.' except when following a volume number)

All elements should be succeeded by a comma except when immediately preceding a parenthesis, and all footnotes should end with a full stop.

So footnotes for critical texts, including those written by a single author (monographs), should look like this:

- Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 61.

- Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel (London: Hogarth Press, 1987), p. 80.

- Seth Koven, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), p. 186.

- Marion Turner, Chaucerian Conflict: Languages of Antagonism in Late Fourteenth-Century London (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007).

- Catherine Hall and Leonore Davidoff, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780-1850, 2nd edn (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 58.

Note:

- These are probably the easiest footnotes, just take care with the punctuation.

- Sometimes there will be different editions of critical texts and if you are using anything other than the first edition, include this information as in example five.

Footnotes for editions of primary texts should look like this:

- Charlotte Brontë, Villette, ed. by Margaret Smith and Herbert Rosengarten (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 212.

- George Eliot, Silas Marner: The Weaver of Raveloe, ed. by David Carroll (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 72.

- Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (London: Penguin, 1994), p. 14.

- Italo Calvino, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller, trans. by William Weaver (London: Vintage 1998), p. 19

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; occasioned by his Reflections on the Revolution in France, 2nd edn (London: J. Johnson, 1790); repr. in The Works of Wollstonecraft, ed. by Janet Todd and Marilyn Butler, 7 vols, The Pickering Masters (London: William Pickering, 1989), V, 1-60 (p. 56).

- The Works of Thomas Nashe, ed. by R. B. McKerrow, 2nd edn, rev. by F. P. Wilson, 5 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958), III, 95-96.

- Daniel C. Eddy, Ministering Women or Heroines of Missionary Enterprise: A Book for Young Ladies, Suitable for Sunday Reading ([n.p.]: Dean and Son, [n.d.]), p. ix.

Note:

- When selecting the edition of a primary text from which to quote, it is best practice to choose a good quality, academic edition that has been properly edited – as in examples one and two rather than example three.

- If you are quoting from an author’s collected works, as in example six, it is obvious who the author is, so there is no need to begin with the author’s name.

- If the book you are quoting from is part of a series, include the series title and number, before the publishing information, as in example five – the Works are published as part of The Pickering Masters series. If the series is not numbered, it is not strictly necessary to include the series title, unless you consider it relevant to your point.

- When referring to a multi-volume work, the number of volumes is given in Arabic numerals (eg ‘5’), but the volume number to which you are referring is given in roman numerals before the page reference (which is not preceded by 'p.' or 'pp.'), as in examples five and six.

- If the work you are quoting is missing some publication information (this can be quite common in works published before 1900) use '[n.p.]' for ‘no place’ or 'no publisher' and '[n.d.]' for ‘no date’, as in example seven. If you have, or think you have the information that is missing (for example, from another source), you can include this in square brackets e.g. [1860], [1860?] instead.

- If you are quoting a work that was published as a complete text in book form originally, but is now being accessed through an edited volume of collected works, follow the form of example five: 'repr. in' stands for ‘reprinted in’, and the page range of the work within the volume is required as well as the specific page reference, which follows in parentheses.

4.2. Chapters in Books

There is really only a need to reference a specific chapter in a book if it is a book which contains chapters written by different authors, such as an edited critical collection.

The information should be given in the following order:

1. Author’s name

2. Title of chapter (in single quotation marks, followed by a comma and the word ‘in’)

3. Title of the book, editor’s name and details of publication (as for a book)

4. The page range within the book for the whole chapter, followed by the specific page cited (in brackets, preceded by 'p.' or 'pp.').

All elements should be succeeded by a comma except when immediately preceding a parenthesis, and all footnotes should end with a full stop.

Examples:

- John Bender, ‘Prison Reform and the Sentence of Narration in The Vicar of Wakefield’, in The New 18th Century: Theory, Politics, English Literature, ed. by Felicity Nussbaum and Laura Brown (London: Methuen, 1987), pp. 180-96 (p. 186).

- Nigel Leask, ‘“Wandering through Eblis”: absorption and containment in Romantic exoticism’, in Romanticism and Colonialism: Writing and Empire, 1780-1830, ed. by Tim Fulford and Peter Kitson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 165-80 (p. 177).

- Elaine Hobby, '"Discourse so unsavoury": Women's published writings of the 1650s', in Women, Writing, History: 1640-1740, ed. by Isobel Grundy and Susan Wiseman (London: B. T. Batsford, 1992), pp. 16-32 (pp. 30-31).

- Catherine Gallagher, ‘The rise of fictionality’, in The Novel, Vol 1: History, Geography and Culture, ed. by Franco Moretti (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), pp. 336-61 (p. 340).

- Gerald Lynch, 'Religion and Romance in Mariposa', in Stephen Leacock: A Reappraisal, ed. by David Staines (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1986), pp. 83-96.

Note:

- Chapter titles are always presented in single inverted commas, while the titles of books are presented in italics. This is the same when referring to titles of books and chapters within the text of your essays.

- Where the title of the chapter includes a novel's title – as in example one – make sure that appears in italics.

- Where the title of the chapter includes a quotation – as in examples two and three – follow the rule for a quotation within a quotation (the title appears in single inverted commas and the quotation appears in double).

- When collections are edited by more than three editors it is acceptable to just include the first editor followed by 'et. al'.

- Remember to include the page range, preceded by 'pp.'

- When you are citing a specific page, include this in parentheses, also preceded by 'p.' or 'pp.'

4.3. Articles in Journals

Footnoting a journal or periodical is similar to footnoting a chapter from a book, but with a few key differences. The information should be presented in the following order:

1. Author’s name

2. Title of article (in single quotation marks but not followed by the word ‘in’)

3. Title of periodical (in italics, in full)

4. Volume number and date of publication as follows: number (date)

6. First and last page numbers of article cited (not preceded by ‘pp.’)

7. Page number of page cited (in parentheses, preceded by 'p.' or 'pp.')

All elements should be succeeded by a comma except when immediately preceding a parenthesis, and all footnotes should end with a full stop.

Examples

- Anna Neill, ‘Buccaneer Ethnography: Nature, Culture, and Nation in the Journals of William Dampier’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 33 (2000), 165-80 (p. 172).

- Bruce Robbins, ‘The Sweatshop Sublime’, PMLA, 117 (2002), 84-97 (p. 95).

- Peter Conradi, 'Iris Murdoch and Wales', Transactions of the Radnorshire Society, 75 (2005), 26-34 (pp. 27-32).

- Gillian Beer, 'The Making of a Cliché: "No Man is an Island"', European Journal of English Studies, 1 (1997), 33-47 (p. 36).

- Urmi Bhomik, 'Facts and Norms in the Marketplace of Print: John Dunton's Athenian Mercury', Eighteenth-Century Studies, 36 (2003), 345-67 (p. 366).

Note:

- There is no need to specify which number or part of a volume you are referring to as the pages across all the numbers of a journal volume are continuous i.e. the Winter edition of PMLA 117, for example, will not start with p. 1.

- Remember to include the page range without 'pp.'

- But do precede the specific page citation in parentheses with 'p.' or 'pp.'

- As for chapters and book titles, remember to present article titles in single inverted commas and journal titles in italics.

4.4. Theatre & Performance

Re-Member Me, written and perf. by Dickie Beau, dir. by Jan Willem van dem Bosch, Almeida Theatre, London, 2 April 2017.

BURGERZ, written and perf. by Travis Alabanza, dir. by Sam Curtis Lindsay, Hackney Showroom, London, 23 Oct. – 3 Nov. 2018 (27 October 2018).

Top Girls, by Caryl Churchill, dir. by Lyndsey Turner, National Theatre, Lyttelton Theatre, London, 26 March 2019.

Depending on the focus of your work, it may be relevant to include details of the full production run in your reference (see e.g. for BURGERZ).

4.5. Footnoting Plays and Poems

Poems and plays are referenced in a similar way to books and chapters in edited collections (author’s name, title of work, editor, publication details). References to plays and long poems should indicate the act and scene (or book/canto), where the quotation occurs as well as line numbers (where given). References to short poems should also include line numbers where available. See below for example of each case in turn. Students taking ESH101 Shakespeare can also see the additional Shakespeare guidance provided by tutors on this course, which deals with the special case of referencing plays from the Norton collection.

Short poems in collections

Treat like chapters in a book, but include part and line numbers if available:

- Wallace Stevens, ‘The Idea of Order at Key West’, in The Norton Anthology of Poetry, 5th edn, ed. by Margaret Ferguson, Mary Jo Salter and Jon Stallworthy (London: W. W. Norton, 2005), pp. 1264-5.

- Sylvia Plath, ‘Tulips’, Ariel (London: Faber and Faber, 1999), pp. 12-14.

- John Donne, ‘The Sun Rising’, in Four Metaphysical Poets, ed. by Douglas Brooks-Davies (London: J. M. Dent, 1997), pp. 15-16 (ll. 11-14).

- Robert Herrick, 'His Farewell to Sack', in Ben Jonson and the Cavalier Poets, ed. by Hugh Maclean (London: Norton, 1974), pp. 110-12 (ll. 29-30).

Long poems

If published alone, treat like a book but include canto and line numbers; if in a collection treat like a chapter in a book:

- William Wordsworth, The Prelude (1805), in The Prelude 1799, 1805, 1850: Authoritative Texts, Context and Reception: Recent Critical Essays, ed. by Jonathan Wordsworth, M. H. Abrams, and Stephen Gill (London: Norton, 1979), xiii. 86-90.

- T. S. Eliot, ‘The Waste Land’, in The Waste Land and Other Poems (London: Faber and Faber, 1999), pp. 21-46 (v. 228-330).

Plays (published alone)

Treat like a book but include act, scene and line numbers where available.

- Henrik Ibsen, A Doll’s House, ed. by Philip Smith (New York: Dover, 1992), ii.

- William Shakespeare, Richard III, ed. by E. A. J. Honigmann (London: Penguin, 1995), iii. 1. 7-16.

Plays in collections

Include the page range followed by the act, scene and line numbers where available.

- Much Ado about Nothing, in The Norton Shakespeare, ed. by Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard, and Katharine Eisaman Maus, 2nd edn (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), pp. 1407-70, iv. 1. 33-34.

- Federico Garcia Lorca, Blood Wedding, in The House of Bernalda Alba and Other Plays, ed. by Christopher Maurer, trans. by Michael Dewell and Carmen Zapata (London: Penguin, 2001), pp. 1-64, iii.

- Sidney Grundy, The New Woman, in The New Woman and Other Emancipated Woman Plays, ed. Jean Chothia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 1-59, i. 1. 272-73.

4.6. Newspapers

References to articles in newspapers require only the date of issue (day, month, year), the relevant section, and the page numbers.

- Jonathan Friedland, ‘Across the Divide’, Guardian, 15 January 2002, section G2, pp. 10-11.

- Michael Schmidt, ‘Tragedy of Three Star-Crossed Lovers’, Daily Telegraph, 1 February 1990, p. 14.

- Charlie Brooker, 'I Hate Macs', Guardian, 5 February 2007, G2 section, p. 11.

- When giving the titles of English-language newspapers or magazines, you should omit an initial The or A, as in all the examples above. The exception to this is The Times which keeps its The.

4.7. Dissertations and Theses

Titles of unpublished theses and dissertations should be placed within single quotation marks, and should not be italicised.

- Ava Arndt, ‘Pennies, Pounds and Peregrinations: Circulation in Eighteenth-Century Literature and Culture’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Queen Mary, University of London, 1999), p. 45.

- Jennie Batchelor, 'Dress, Distress and Desire: Clothing and Sentimental Literature' (unpublished doctoral thesis, Queen Mary, University of London, 2002), p. 32.

- Kate Harris, ‘Ownership and Readership: Studies in the Provenance of the Manuscripts of Gower’s Confessio Amantis’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of York, 1993), p. 10.

- Stephanie Hovland, ‘Apprenticeship in Later Medieval London, c.1300-c.1530’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London, 2006), p. 101.

4.8. Online and Electronic Sources

The method of citation for electronic resources follows the model for print publications. Electronic citations are troubling because the internet does not offer stable, finished editions (changes to web-sites may be made incrementally and frequently). If using an on-line full-text database, always refer to the stable URL.

Information – as much as is available – should be given in the following order:

1. Author’s name

2. Title of item

3. Title of complete work/resource

4. Publication details (volume, issue, date)

5. Full web address (Universal Resource Locator (URL)) in angle brackets

6. Date at which the resource was consulted (in square brackets)

7. Location of passage cited (in parentheses, in most intelligible form).

You will encounter websites with substantially fewer details than this (many sites are anonymous, untitled, and provide no publication information). If you encounter such a site, ask yourself first whether it is an appropriate resource to be citing in your work. If you determine it is, provide as many of the above details as you can, as well as any other details which would help your reader to track down your source.

Online Book

(either an electronic text of a printed book or a book-length electronic publication such as a hypertext fiction)

1. Geoff Ryman, Two Five Three: A Novel for the Internet, April 1999 <http://www.ryman-novel.com/>; [accessed 9 July 2000], (Car 4 passengers).

Online articles

1. Clara Tuite, ‘Cloistered Closets: Enlightenment Pornography, The Confessional State, Homosexual Persecution and The Monk’, Romanticism On the Net, 8 (November 1997) <http://www.erudit.org/revue/ron/1997/v/n8/005766ar.html>; [accessed 2 August 2008], (section II).

2. 'WG Sebald (1944-2001)', Guardian Unlimited <http://books.guardian.co.uk/authors/author/0,,-195,00.html>; [accessed 12 December 2006].

3. Ivan Keta, '“The Hitchcock Film to End All Hitchcock Films”: Intertextuality and the Nature of the World in North by Northwest', Common Room, 15.1 (2012), <http://departments.knox.edu/engdept/commonroom/Volume15.1/Ivan_Keta.html>; [accessed 31 August 2012] (para. 2).

4. Catherine Price, '"Mom Lit" is Born', Salon.com (19 December 2006) < http://www.salon.com/mwt/broadsheet/2006/12/19/mom_lit/index.html>; [accessed 22 December 2006].

Online databases

1. Emily Dickinson, ‘A Light Exists in Spring’, in Literature Online <http://lion.chadwyck.co.uk> [accessed 17 October 2012].

2. George Lyttelton, Dialogues of the Dead (London: W. Sandby, 1760), p. 45, in Googlebook <http://books.google.com/>; [accessed 12 August 2008].

Note:

- A digital facsimile of a printed edition should include a full reference to the relevant print edition

Personal web-sites

1. Brycchan Carey, ‘Ignatius Sancho Homepage’ <http://www.brycchancarey.com/ sancho/index.htm> [accessed 10 July 2002].

2. Stephen Alsford, 'History of Medieval Lynn: Origins and Early Growth', Medieval English Towns (2012) <http://users.trytel.com/~tristan/towns/lynn1.html>; [accessed 31 August 2012] (para. 4).

Citations from E-Book Readers (such as Kindle etc)

The department suggests that tablet e-book editions (such as for Kindle) do not offer a good basis for scholarship, and does not recommend using them in assessed work. However, if for some reason you need to cite an e-book edition, include the format and any page locator information provided with it (a section title or a chapter or other number, such as location or percentage). Eg:

1. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (New York: Penguin, 2007), Kindle edn, location 2684.

4.9. Film and Cinema

The reference should contain the relevant important information, including as a minimum: title, director, distributor, and date. Other information (producer, artists) may be provided if it is relevant.

- The Grapes of Wrath, dir. by John Ford (20th-Century Fox, 1940).

- I Walked with a Zombie, dir. by Jacques Tourneur, prod. by Val Lewton (RKO Radio Pictures, 1940).

- ‘Storytelling: Trailer’, Storytelling, dir. by Todd Solondz (New Line Home Video, 2001 [on DVD]), Chapter 1.

- A Night at the Opera, dir. by Sam Wood, perf. by the Marx Bros (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1935), on DVD (Warner Home Video, 2004).

Note:

- As in example three, it is good practice to provide as much information about the specific location of what you are citing as possible.

4.10. Manuscripts

A reference to a manuscript should include the following information:

Details of the repository/library/archives/collections where the manuscript is. This should include:

1. The location of the repository (followed by a comma)

2. The name of the repository (followed by a comma)

3. The name or reference number of the manuscript (in full, typically preceded by MS, followed by a comma)

4. Folio or page numbers (preceded by 'fol.'/'fols' or 'p.'/'pp.', followed by a full stop)

Examples:

- Cambridge, Trinity College, MS 0.9.38, fol. 72v.

- New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M.126, fol. 4r.

- London, National Archives, MS SC 8/199/9925.

Note:

- For many manuscripts, we cite folio rather than page numbers – as in examples one and two above. While a single leaf in a modern printed book has two page numbers (one for the front and one for the reverse of the leaf), a leaf (or folio) in a manuscript has a single folio number. The front and back are distinguished by the letters r and v: r for recto (the front), and v for verso (the reverse). Folio numbers are given in the form: 17v or 16r. Note that the 'v' and 'r' abbreviations do not take a full stop (though, as in the examples above, they typically occur at the end of a citation and are – for that reason – followed by a full stop).

- Not all MSS will have a folio number: some will be paginated, while others might just be a single sheet as in example three.

4.11. Interviews and Personal Communications

Lois Weaver, interview with the author, Queen Mary University of London, 8 March 2019.

Maria Guevara, 'New Spanish Publications' (Email to Carlos Pererra, 16 July 2015).

5. Limiting footnotes

Footnotes count towards your essay's wordcount, so you might want to think about how to limit the number and length of your footnotes. Here are some acceptable methods to do this:

Shortening titles

The majority of titles should be given in full as they appear on the title page. Where a work has a very long title, it is acceptable to abbreviate it:

John Lindsay, The Evangelical History of our Lord Jesus Christ: Harmonized, Explained and Illustrated with Variety of Notes Practical, Historical, and Critical, 2 vols (London: Newbery and Collins, 1757).

Instead of:

John Lindsay, The Evangelical History of our Lord Jesus Christ: Harmonized, Explained and Illustrated with Variety of Notes Practical, Historical, and Critical. To which is Subjoined, an Account of the Propagation of Christianity, and the Original Settlement and State of the Church. Together with Proper Prefaces, and a Compleat Index. The Whole Dedicated to the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons in Parliament Assembled, 2 vols (London: Newbery and Collins, 1757).

Subsequent references

Full publication details must be given on the first occasion a source is cited. In all subsequent references, though, the shortest intelligible form may be used. This will normally be the author’s surname followed by the page number; if this is ambiguous (because you are citing two books by the same author or two authors with the same surname) then repeat the title in a shortened form:

- Bender, p. 186.

- Gallagher, 'Rise of Fictionality', p. 341.

- Storytelling, Chap. 5.

- Tuite, ‘Cloistered Closets’, Sect. 3.

Clustering references

References clustered together in the text, within one paragraph, can normally be grouped together in one footnote, as long the referenced work remains clear.

In-text references

For a series of references to the same text, where there is no ambiguity as to what is being referenced, it is possible to incorporate page/line references into the text, normally in parentheses after quotations (for example '(p. 23)'). In order to do this, you must state after the first full citation of the text that 'Subsequent references to this edition will appear parenthetically within the text'.

Note:

- An example of a footnoted document, using cluster and in-text references, can be found here.

- Footnotes need not repeat information already supplied in the text of the essay leading up to the quotation.

- The abbreviated latin phrases ‘loc. cit.’, ‘op. cit.’ and ‘ibid.’ are confusing to the reader and should not be used.

6. Bibliographies

At the end of your essay, make sure to include a bibliography which lists all works consulted in the course of researching and writing your essay. At the very least make sure that it includes all the works you have referenced.

The format of bibliography entries is almost the same as for footnotes, just note the following:

- Bibliographies are lists, so neither the items in the list nor the bibliography as a whole need to end with full stops.

- Bibliographies are arranged in alphabetical order, organised by author surname.

- Given this, each entry should begin with the author's surname (rather than first name as in footnotes).

- If the source has two authors, only the first should be reversed as in the final example below.

- If you have referenced more than one source by the same author, replace the author field with a long dash for subsequent entries. This is not shown below, but can be seen in the bibliography example document.

- Apart from the changes in terms of author names and full stops, bibliography entries follow the same rules as for footnotes - remember to include page ranges for chapters, journal articles and anything published in collections - though clearly there is no need for specific page/line references.

For example:

Alsford, Stephen, 'History of Medieval Lynn: Origins and Early Growth', Medieval English Towns (2012) <http://users.trytel.com/~tristan/towns/lynn1.html>; [accessed 31 August 2012]

Bender, John, ‘Prison Reform and the Sentence of Narration in The Vicar of Wakefield’, in The New 18th Century: Theory, Politics, English Literature, ed. by Felicity Nussbaum and Laura Brown (London: Methuen, 1987), pp. 180-96

Brontë, Charlotte, Villette, ed. by Margaret Smith and Herbert Rosengarten (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990)

Conradi, Peter, 'Iris Murdoch and Wales', Transactions of the Radnorshire Society, 75 (2005), 26-34

Friedland, Jonathan, ‘Across the Divide’, Guardian, 15 January 2002

Hall, Catherine and Leonore Davidoff, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780-1850, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2002)

See our bibliography example document for how to format a bibliography.

7. Credits

This style guide was created by Angharad Eyre with additional material provided by Markman Ellis, Rob Ellis, and Sam Solnick. Additional Shakespeare material was provided by Pete Mitchell and David Colclough.

It was created as part of the SED's Student Writing Resource Project, led by Professor Catherine Maxwell and funded by the Westfield Fund for Enhancing the Student Experience. The project was supported by SED e-Strategy Managers Richard Coulton and Matthew Mauger.