Malta - MBBS Year 4 - Information Portal

Section outline

-

Malta Medical Professionalism Curriculum

-

BB Neurology

-

BB Ophthalmology

-

BB Psychiatry

-

CSP ENT & Ethics

-

Global Health

-

HD Child Health

-

HD Obstetrics & Gynaecology

-

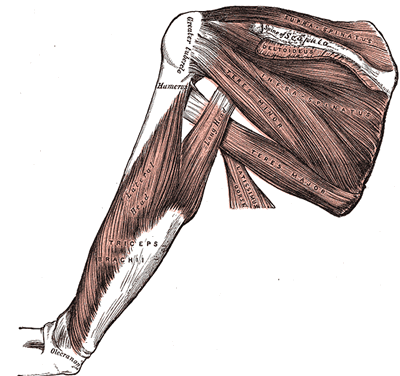

Loco Musculoskeletal

-

Loco Geriatric Medicine

-

LOCO Dermatology

-

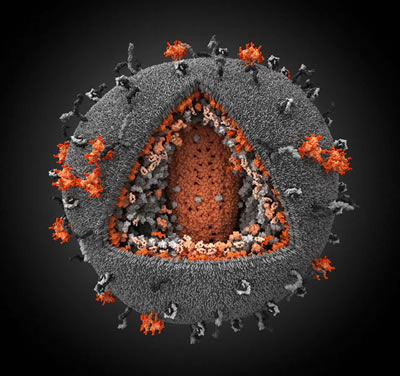

HIV & Sexual Health

-

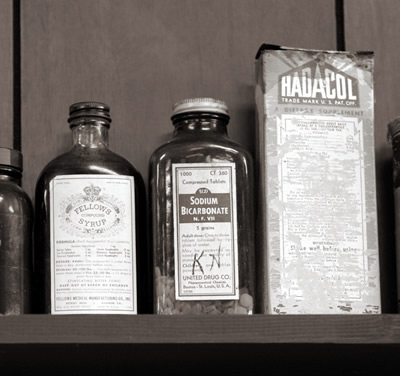

Clin/Pharm Therapeutics

-

Student Selected Component (SSC)

-

GP4 Placement

-

Exams and Assessment

-

Library Information and Resources

-

Academic Support - Remediation Programmes

-

Please note, you will only be able to get a replacement ID card if you are temporarily or fully enrolled. If you are eligible for re-enrolment, you will not be able to get a replacement ID card until you have completed the re-enrolment task.

If you need a replacement ID card, please check which of the circumstances in the drop-down tabs below are applicable to you and read the guidance on what you need to do in order to get your new ID card.

-

-

-

514.7 KB

-

Virtual Primary Care is a general practice based educational resource providing students with access to a video library of authentic primary care consultations. Every consultation has been tagged for clinical and educational content and is accompanied by a brief summary, associated learning points and references, making it a very useful asset for your studies.

-

-

12.8 MB

-

603.8 MB

-

81.8 MB

-

-

This page shows how to use PebblePad during this academic year.

-

-

If you wish to raise a concern and speak up you should do so using Report and Support: https://reportandsupport.qmul.ac.uk/

The process below outlines what you can expect from the School once you have submitted your concern via Report and Support. If you are unsure what to do you are encouraged to contact a member of staff within the School first and there is a list of helpful contacts on page 3 of the process.

The Raising Concerns & Speaking Up module has been created to support you in raising concerns about things you may have witnessed or experienced.

QMPLUS MODULE LINK: https://qmplus.qmul.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=16177